The region and Lake Myvatn (literally: lake of flies) abound in very interesting rock formations, many of which are unique in the world. This is due to the specific combination of volcanic activity, glaciers and the lake itself. We can divide the geological history of this region into four main periods. See how this remarkable area was formed.

Time of last glaciation

The general outline of today’s Lake Myvatn and its immediate surroundings was formed during the last glaciation, in the era known as the Pleistocene. At the end of the glaciation, about 10,000 years ago, the Mývatn basin was covered by a glacier, which formed the Reykjahlid moraines. They are still visible today at the northern end of the lake. The western shore is a basalt ridge formed in the early Pleistocene, or about 2 to 2.5 million years ago. The eastern shore, on the other hand, is formed by rocks of the so-called Moberg Formation, which formed at the end of the Pleistocene (about 780,000 to 10,000 years ago)[1]

Many of the hills around the lake were formed as a result of eruptions occurring under the ice sheet during the Ice Age. The eruptions that managed to break through the ice formed the table mountains (Bláfjall, Sellandafjall, Búrfell, Gaesafjoll mountains). In turn, those that remained hidden under the ice gave rise to mountain ridges made of solidified lava, the so-called hyaloclastite (Vindbelgjarfjall, Námafjall, Dalfjall, Hvannfell mountains). You can read about the specifics of sub-ice eruptions in our separate article: How Iceland’s volcanoes work

When the glacier began to melt a post-glacial lake was left behind. Its existence had a key influence on how the area and shores of today’s Lake Mývatn were later formed.

The post-glacial volcanic activity in the area is divided into three cycles: the Ludent, Hverfjall and Mývatnseldar. They were separated on the basis of tephrachronology, a method that determines the age of sediments based on small layers of pyroclastic materials (mainly ash). Here, these ashes were provided by eruptions of the Hekla volcano, which lies far to the south of the island (we write more extensively about it here: Hekla – Queen of Icelandic Volcanoes).

Lúdent cycle

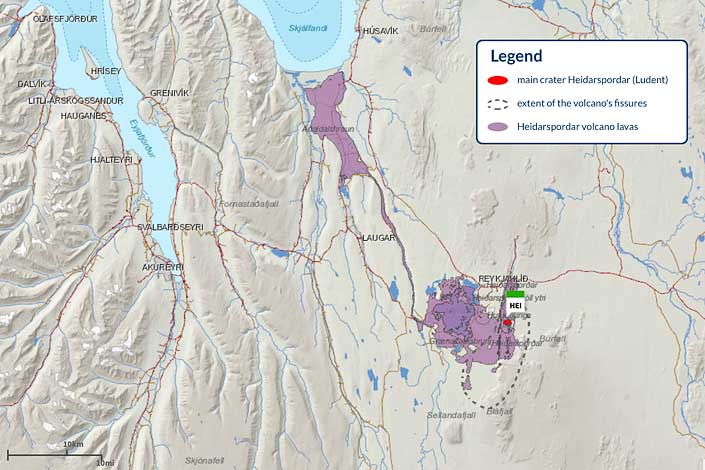

The Lúdent cycle began after the end of the Ice Age, about 11,000 years ago. Ludent crater, which is a truncated tuff cone and part of the larger Heiðarsporðar system, was formed just during this cycle. The eruption that formed it was followed by a series of smaller fissure eruptions.

Hverfjall cycle

The present shape of Lake Mývatn was formed about 2,300 years ago by a large fissure eruption spitting out basaltic lava during the second cycle of volcanic activity, known as the Hverfjall cycle. This cycle began 2,500 years ago with a gigantic yet brief explosive eruption. It was after it that the tufa crater Hverfjall (also called Hverfell) remained to the east of the lake. Hverfjall is about 150 meters high and just over 1 km in diameter. The volume of its volcanic formations is about 130 million m3 (or about 0.13 km3).

In contrast, the largest eruption of this cycle occurred about 2,000 years ago from the Threngslaborgir-Ludentsborgir row of craters. These are often pointed to as a textbook example of a row of volcanic craters. As a result of this eruption, the so-called “younger” Laxa lava field (Laxararhraun) was formed. This younger lava over a large area covers the lava of the older Laxararhraun field, but it does not reach as far south and southeast, instead it flowed further to the north, all the way to the ocean in the Skjalfandi Bay area, about 50 km northwest of the lake. It was then that the lava – acting like a dam – gave the current shape to Lake Mývatn, as well as lakes Sandvatn, Grænavatn and Arnarvatn. This lava cover consists mainly of so-called block lava (apalhraun), covers 220 km2 and has a volume of 2.5 km3

Viti cycle

The third cycle of volcanic activity – the Viti cycle – began with eruptions named Mývatnseldar (literally, the fires of Mývatn) between 1724 and 1729. The first of these eruptions – on the morning of May 17, 1724 – was a short maar-type explosion and formed, among other things. among others, the Víti crater lake in the Krafla complex (not to be confused with the crater and lake of the same name in the Askja complex further east). Lava from this eruption created the Leirhnjúkur lava field extending all the way to the northern end of Lake Mývatn and destroyed two farms that existed there at the time.

The eruptions of the Mývatnseldar cycle resemble in their characteristics the recent eruptions of the Krafla volcanic complex in 1975-1984. The source of both of these eruptions is the central volcano located between the Krafla caldera and Gaesafjoll. Deep within this volcano is a volcanic chamber from which hot magma periodically explodes through fissures that cross the surface from north to south.

Recent volcanic activity is characterized by periods of slow uplift alternating with shorter periods of rapid landslides, accompanied by underground magma explosions, cleft formation, earthquakes and eruptions.

In contrast, the sulfatar field Namafjall Hverir according to geological studies[2] has existed in its current location “since the beginning,” i.e. for at least 11,000 years. Sulfatars are a type of exhalation, i.e. places where hot gases and vapors escape to the surface. If you want to learn more about them, take a look at this article: Stunning effects of Iceland’s volcanism

Photos of the area around Lake Myvatn

Read more

If you want to see what interesting places and attractions lie around Lake Myvatn, go to this article: Myvatn – an unusual lake among volcanoes or browse this list of articles about the most interesting places in the area: Surroundings of Lake Myvatn

If you are more interested in the geology of Iceland as a whole, the specifics of the volcanoes here, and information about the amazing effects of volcanism in Iceland, go to the series of guides starting with this article: How Iceland was formed – the geology of the island in a nutshell

Bibliography

[1] Sveinn P. Jakobsson and Magnús T. Gudmundsson, Subglacial and intraglacial volcanic formations in Iceland, JÖKULL No. 58, 2008.

[2] Thorarinsson, Sigurdur. “The Postglacial History of the Mývatn Area.” Oikos, vol. 32, no. 1/2, 1979, pp. 17-28. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3544218 Accessed June 5, 2020.