A volcano is as common a thing in Iceland as, say, a field or a forest in Poland – they are practically everywhere if you just leave the city. Mostly, of course, they are cones of volcanoes that erupted even thousands of years ago, but remember that for volcanologists, any volcano that has erupted at least once in the last 10,000 years is still an active volcano.

If you are looking for up-to-date information on the latest eruption – Meradalir – from August 2022, you can find it here: Iceland’s newest attraction – Meradalir eruption

However, Iceland also has many volcanoes that are active in a much more mundane sense – those whose last eruption took place, say, 100 years ago, or in some cases only 10 or 20 years ago. In the past 100 years we’ve had as many as 38 eruptions in Iceland, or more than one every three years.

In this article, we present these largest and most famous eruptions from historical times.

How many volcanoes are there in Iceland

In everyday language, “volcano” to us means a mountain visible on the earth’s surface, formed by a volcanic eruption. To volcanologists, however, it is just a “volcanic cone” (or volcanic mountain), and a volcano is a whole underground system of chambers and channels that collect lava. In this sense, one volcano can have (and in Iceland has) very many cones, or volcanic mountains.

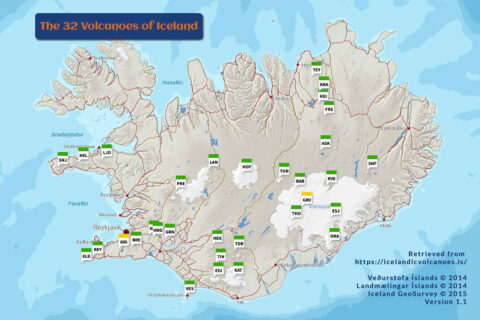

Although almost every mountain you see in Iceland is a volcanic mountain (so there are hundreds, if not thousands of them), according to the classification of the Institute of Earth Sciences at the University of Iceland [8] today we distinguish “only” 32 volcanoes in all of Iceland. You could say these are rather ‘volcanic systems’ than individual volcanoes, but it’s the official classification.

As you can see from the map above, at the time of writing this article, two volcanoes – Krýsuvík and Grímsvötn – were highlighted in yellow. This means that they pose a potential threat to air traffic, due to their ongoing activity.

How often volcanoes erupt in Iceland

In the rock footprints, such as by examining underground rock layers today, scientists can determine the dates and approximate size of many eruptions from as many as 100,000 years ago and more.

But naturally, we have much more information about the course and effects of eruptions from the last millennium – since Iceland has been inhabited. During this time eruptions have occurred on average, every 3-4 years. The younger the eruptions are, we also have increasingly reliable and accurate descriptions of the course of the events themselves.

Of course, volcanic activity in Iceland continues non-stop and various smaller effects of volcanoes – such as small earthquakes – are felt daily or almost daily. You can read more about the various – other than eruptions – effects of volcanism in Iceland in this article: Stunning effects of Iceland’s volcanism Meanwhile, we wrote about how volcanoes work here: How Iceland’s volcanoes work.

How the force of a volcanic eruption is measured

Volcanic eruptions can be described in a number of ways, but the primary measure used for this is the so-called Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI), which describes several parameters related to the eruption:

- volume of pyroclastic materials produced,

- the height of the cloud of materials ejected into the atmosphere

- description of the explosion

As of today, the index ranks eruptions on a scale of 1 to 8, since no eruption stronger than 8 has yet been recorded. Besides, there have been very few eruptions with a magnitude of 8, and all of them a very long time ago. The most recent one – of New Zealand’s Taupo volcano – took place almost 30,000 years ago. The largest relatively recent eruption was that of Indonesia’s Tambora volcano in 1815, with a magnitude of 7.

The disadvantage of the VEI index is that it describes eruptions based on the pyroclastic materials fired, and many eruptions do not produce any. These are lava (efluvial) volcanoes, from which mainly – or only – lava is spewed during an eruption. Such eruptions are therefore excluded from evaluation according to the VEI index. This gives some leeway in determining, for example, which eruption in history was the largest or most severe….

From 1982 data describing the strongest eruptions around the world on the basis of VEI, 122 eruptions with VEI values above or equal to 4 have been recorded since 1500, with as many as 14 just in Iceland.

Strongest volcanic eruptions in Iceland

The strongest confirmed Icelandic eruptions according to the VEI index are the 1477 Bardarbunga eruption and the 8277 BC Grimsvotn eruption. Both are rated 6 on the VEI scale [9].

| Iceland eruptions by VEI | ||

|---|---|---|

| Volcano | Year of eruption | Power according to VEI |

| Bardarbunga | 1477 | 6 |

| Grimsvotn | 8230 BC | 6 |

| Assyria | 1875 | 5 |

| Katla | 1755 | 5 |

| Katla | 1721 | 5 |

| Katla | 1625 | 5 |

| Oraefajokull | 1362 | 5 |

| Katla | 1262 | 5 |

| Hekla | 1104 | 5 |

| Hekla | 1100 BC | 5 |

| Hekla | 2310 BC | 5 |

| Hekla | 4110 BC | 5 |

| Hekla | 5150 BC | 5 |

| Assyria | 8910 BC | 5 |

As you can see, most of these strongest eruptions were recorded by Hekla – Queen of Icelandic Volcanoes. The list includes 38 more eruptions with a magnitude of 4, 35 eruptions with a magnitude of 3, 183 eruptions with a magnitude of 2 or lower, and as many as 227 eruptions without an assigned VEI index.

Hazards associated with volcanic eruptions

The main danger during volcanic eruptions is pyroclastic materials (known as tephra) shooting out of the crater and falling to the ground. These are all loose materials ejected from the volcano – from so-called volcanic bombs (from 6 cm to even 1 m in diameter!), to very fine ashes capable of persisting in the atmosphere for a long time (and, for example, posing a danger to aircraft).

Every volcanic eruption is a dangerous event, but the level of danger depends on several factors:

- The first is how long the eruption lasts and how much ash will be ejected during the eruption.

- The second factor is the height to which the dust will be ejected, as this is related to its subsequent spread in the area, region and even around the world. In this regard, atmospheric factors such as wind (its direction and strength) or rain (which accelerates the fall of dust and reduces its range) are very important.

- Another direct threat is the lava flowing from the volcano. Depending on its composition, it can be thin (in which case it flows quickly and there is much less time to escape) or viscous – in which case it slowly flows down the slopes.

- When volcanoes erupt, lightning is also a threat. Atmospheric discharges can be really strong, and lightning can strike as far as 30 km from the volcano.

- Water pollution, mainly halides, is also very dangerous. They cause contamination of water, for example: fluoride, which is dangerous for humans and animals.

- When some volcanoes erupt, huge amounts of greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide and methane are ejected. Many other gases spewed from volcanoes also pollute the atmosphere.

- Finally, a danger associated with volcanic eruptions, which is somewhat peculiar to Iceland, are also very violent glacial floods – called jokulhlaup here. After all, Iceland is located so far north that many of the local volcanoes are covered by glaciers. When such a volcano erupts, the heat that rises from it heats up gigantic areas of the glacier, causing it to melt. Often water accumulates over the crater and does not immediately find an outlet. If enough of it accumulates, when it finally finds an outlet, it breaks one of the caldera’s banks, a sudden, huge, very fast and catastrophic flood occurs, which is a flood of short duration, but of a force incomparable to any ‘ordinary’ one. You can read about the course of one such flood – a fairly recent one in 1996 – here: Jokulhlaup of the Grímsvötn volcano (1996). Crouched to the ground, the mighty spans of the iron bridge over the Skeidara River, destroyed during this flood, can be (and are worth seeing!) near the Skaftafell Nature Reserve.

When considering the extent of the destruction of a given eruption, it should also not be overlooked that eruptions near human settlements and settlements are much more severe than those that occur far from human concentrations. Eruptions destroy farmland, poison water, and fire burns buildings and settlements. In a country like the former Iceland, virtually every major volcanic eruption has led to famine.

Iceland’s largest volcanic eruptions

When evaluating the strength and significance of a given eruption, it is difficult to adopt a single criterion. We can easily find many such “greatest” explosions. What matters, after all, is not only the strength and enormity of the explosion itself (and even these can be measured differently), but also the impact it had on the life of Iceland, Europe and the world. You can also find many interesting facts about the history of Icelandic volcano eruptions in this article: The Stunning Effects of Iceland’s Volcanism.

Below is a list of the most important volcanic eruptions in Iceland due to various factors.

Bárðarbunga – strongest eruption (1477)

Bardarbunga-Veidivotn is a volcanic system with the central volcano Bardarbunga (Iceland’s second highest peak). It has recorded as many as 24 eruptions since 870, making it the second most active volcanic system in historic times in Iceland. It is estimated that this volcanic system may have undergone up to nearly 400 eruptions in the past 10,000 years.

Bardarbunga-Veidivotn is a volcanic system with the central volcano Bardarbunga (Iceland’s second highest peak). It has recorded as many as 24 eruptions since 870, making it the second most active volcanic system in historic times in Iceland. It is estimated that this volcanic system may have undergone up to nearly 400 eruptions in the past 10,000 years.

The main volcano and most of the rift that accompanies it are located under the Vatnajokull glacier, and most volcanic events are described in this area. Their main effect is very extensive glacial floods (jokulhlaups).

The last eruption in this volcanic system occurred in 2014, however, the one with the highest VEI index (6) occurred in 1477. As a result of this eruption, the volcano emitted about 10 km3 of pyroclastic materials, which covered all of Iceland with at least a 1 cm layer, and about 50% of the island with a layer of as much as 10 cm! [8]

Öræfajökull – most ashes (1362)

Oraefajokull is Iceland’s highest peak (2110 meters above sea level) and one of six volcanic systems covered by the country’s largest glacier, Vatnajökull.

Oraefajokull is Iceland’s highest peak (2110 meters above sea level) and one of six volcanic systems covered by the country’s largest glacier, Vatnajökull.

It is this volcano that is responsible for the largest explosive eruption in historic times in Iceland. This eruption took place in 1362, and in the VEI index, the eruption is numbered 5 [9], which is lower than the strongest eruptions of Bardarbunga and Grimsvotn. However, it was during this particular explosion that the largest amount of tephra was ejected into the atmosphere. The total volume of ejected steam, gases and volcanic ash is estimated at as much as 10 km3 According to current estimates, the height of the ash cloud could have reached as high as 35 km (sic!), and pyroclastic materials from this eruption can be found today in Greenland, Norway and Ireland, among other places.

The 1362 eruption took a huge toll, as the area was quite heavily populated (for the time), and the eruption caused the complete destruction of everything in a radius of at least 20 km. Human buildings were destroyed in a much larger area, also because the eruption was accompanied by a strong earthquake and glacial flooding, and the immediate area – up to the town of Hofn – was covered with about 10 centimeters of ash. It is believed that this was one of the more deadly eruptions. Between 50 and as many as 300 people lost their lives during it, and residents’ habitats and about 30 farms were also destroyed.

The 1727 eruption (VEI 4) was also similarly strong, though less tragic in its consequences. Three people died because of it, and the most devastating element of this eruption was again the gigantic and very violent glacial floods.

Katla – largest total quantity of magma

Katla is a volcanic system located in the southern part of the island. It is located under the cap of the Myrdalsjokull glacier. The Katla system is still active and the third most active in historical times. It has erupted at least 21 times since the 9th century, with the last of the eruptions occurring in 1918. Almost all eruptions have been fissure, subglacial and phreatomagmatic. Since 870, this volcano has produced as much as 25 km3 of magma (the most in all of Iceland!)

Katla is a volcanic system located in the southern part of the island. It is located under the cap of the Myrdalsjokull glacier. The Katla system is still active and the third most active in historical times. It has erupted at least 21 times since the 9th century, with the last of the eruptions occurring in 1918. Almost all eruptions have been fissure, subglacial and phreatomagmatic. Since 870, this volcano has produced as much as 25 km3 of magma (the most in all of Iceland!)

The largest eruption of Katla took place in 934, and its strength according to the VEI index was 4.

Since Katla is covered by a glacier, the main danger associated with eruptions of this volcano is yokulhlaups – glacial floods. Despite being such a dangerous and very active volcanic system, only one fatality has been attributed to it in history. It was a person struck by lightning (as far as 35 km from the volcano!).

Hekla – most strongest explosions

Hekla is one of the most famous volcanoes in all of Iceland. It can be said that it made it to this list “for the whole thing.” As you can see from the table above, it is Hekla that is responsible for most of the country’s most powerful eruptions. Since 870, 23 eruptions have been recorded here, ranking it third in terms of activity at the time of settlement. Hekla also erupts fairly regularly, with at least 1 eruption every 50 years during the period studied.

Hekla is one of the most famous volcanoes in all of Iceland. It can be said that it made it to this list “for the whole thing.” As you can see from the table above, it is Hekla that is responsible for most of the country’s most powerful eruptions. Since 870, 23 eruptions have been recorded here, ranking it third in terms of activity at the time of settlement. Hekla also erupts fairly regularly, with at least 1 eruption every 50 years during the period studied.

Between 1766 and 1768, the largest known eruption of Hekla happened, during which 1.3 km3 of magma was spewed out. On the other hand, the strongest according to the VEI index was the eruption of 1104, numbered 5. In contrast, the eruption of 1300 caused the poisoning of many livestock and famine on the island. In contrast, the most costly eruption of Hekla is considered to be the one in 1970, when more than 8,000 sheep died due to poisoning from fluoride escaping from the volcano, and the total losses associated with the eruption were estimated at 1-2 million euros.

It is particularly interesting that at the end of the 20th century Hekla erupted five times, almost evenly every 10 years: in 1970, 1980, 1981, 1991 and 2000. The eruptions tended to be short-lived (30 minutes to 2 hours) and not very strong (VEI 2-3), and we haven’t had one yet in the 21st century. However, the civil service warns very seriously against Hekla, because in the case of this volcano, pre-shocks or other signals announcing an impending eruption even occurred only 30 minutes before the eruption!

Grimsvotn-Laki – most deadly (1783)

The Grimsvotn volcanic system is the most active volcanic system in all of Iceland. Some 70 eruptions have been recorded here since 870, which together have produced some 21 km3 of magma. According to recent studies, about 10,000 years ago this system may have produced several large eruptions of VEI scale 5 to 6.

The Grimsvotn volcanic system is the most active volcanic system in all of Iceland. Some 70 eruptions have been recorded here since 870, which together have produced some 21 km3 of magma. According to recent studies, about 10,000 years ago this system may have produced several large eruptions of VEI scale 5 to 6.

The most recent eruption occurred in 2004, but it is not the one that is best known. The one that is most often described, and is treated as the largest of all certain eruptions, happened between 1783 and 1784. It is numbered 4 in the VEI index, and is commonly known as the Laki eruption.

It was an eruption from a fissure as long as 27 km, located on the non-ice-covered part of the entire system. During this one eruption alone, an estimated 14.7 km3 of magma was spewed out, spreading over an area of as much as 565 km2. About 120 Mt of sulfur dioxide also escaped into the atmosphere. The resulting cloud took up about 25% of the entire northern hemisphere and had a very negative impact on the environment and climate.

It is also the deadliest eruption in Iceland’s history Although not a single person died during the eruption itself, a great many farm animals perished, which in turn caused a huge famine throughout the country in the following years. It is estimated that nearly 8,700 people lost their lives due to the eruption, and between 1783-86 the population of the entire state declined by as many as 10,500 people due to famine, epidemics and a drastic decline in births.

Eyjafjallajökull – costliest explosion (2010)

Eyjafjallajokull is an ice-covered stratovolcano and the perpetrator of perhaps the most famous eruption currently taking place in Iceland.

Eyjafjallajokull is an ice-covered stratovolcano and the perpetrator of perhaps the most famous eruption currently taking place in Iceland.

Its eruption, after 187 years of dormancy, occurred quite recently, on March 20, 2010. The entire eruption began with a small earthquake, after which a 150-meter fountain of lava flowed from a 100-meter fissure and from its 12 craters simultaneously. The lava had a temperature of 1,200 ºC, and the dust cloud rose to 7,000 meters. The entire outpouring lasted three and a half weeks and 500 people had to be evacuated because of it.

About a month later – April 14, 2010 – there was another eruption this time from the very top of the volcano, located under the glacier of the same name. The eruption caused a so-called phreatomagmatic eruption, in which (after the relevant part of the glacier melted) a huge ash cloud under high pressure shot into the stratosphere. The cloud caused huge disruptions to air traffic throughout virtually all of Europe, and as Iceland lies centrally on the route of planes flying between Europe and North America, connections to the US and Canada were also paralyzed.

It is estimated that up to nearly 50% of all worldwide passenger flights were canceled in the days or so after the explosion. Some 10 million passengers were unable to make or continue their journeys. Losses to airlines are estimated at 1.5 – 2.5 billion euros [6].

Compared to eruptions of the 18th or 14th centuries, the Eyjafjallajokull eruption was not particularly large. It produced ‘only’ 0.27 km3 of pyroclastic materials and about 0.023 km3 of lava. However, it was significant that the ash from this eruption was very fine, making it very long in the air in the middle of the busiest air route and over much of Europe.

Krafla – the Fear of the North

Krafla has had only two so-called episodes in its history. Both took place in the last 250 years, and both were devastating to the local community.

Krafla has had only two so-called episodes in its history. Both took place in the last 250 years, and both were devastating to the local community.

The first, from 1724-1729, is called the Myvatn Fires, and the second, from 1975-1984, is called the Krafla Fires. A total of about 5 km3 of magma was ejected during both events. The eruptions during both episodes were related to the outflow of lava itself (associated with rift expansion), making most of them not included in the VEI index at all (and those that are included there are given an index of 0 or 1).

Not a single person was hurt in either incident, but both were devastating to the local community. The Myvatn Fires, according to contemporary accounts (primarily by Pastor Jon Saemundsson [10]), in addition to the lava flow itself, were accompanied by, among other things, strong earthquakes that destroyed many buildings, killed many livestock and forced residents to move out of the area. However, due to the low population density and the lack of expensive buildings or infrastructure that the eruption could destroy, the total damage from the Myvatn Fires was limited.

In contrast, the 1975-84 eruption was much more costly. The total value of the damage caused was estimated at as much as 70 million euros. A large share of this amount was due to structural damage to a geothermal power plant under construction nearby at the time (it was Kröflustöð – Iceland’s largest geothermal power plant). The damage delayed its full startup by as much as two decades.

For the scientific world, however, it was a very valuable eruption. It yielded a great deal of information on the mechanics of volcanoes in Iceland’s rift zone.

Vestmannaeyjar – creator of its own archipelago

Vestmannaeyjar is Iceland’s youngest volcanic system. It lies in the so-called eastern volcanic zone and takes its name from the archipelago it de facto created. It consists of many basalt islands and underwater cones on Iceland’s southern shelf. Due to its young age, it is the site of a great many famous eruptions from the 20th century.

Vestmannaeyjar is Iceland’s youngest volcanic system. It lies in the so-called eastern volcanic zone and takes its name from the archipelago it de facto created. It consists of many basalt islands and underwater cones on Iceland’s southern shelf. Due to its young age, it is the site of a great many famous eruptions from the 20th century.

The first of the famous eruptions of the Vestmannaeyjar volcano took place in 1963-1967, and in its aftermath, truly before the eyes of the whole world, the island of Surtsey was formed. The island was immediately inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List and is free from human interference. Only a narrow circle of scientists have access to it, and the island is a site for research on how plants and animals colonize areas of magma eruptions.

The second famous eruption was the one in 1973, on the archipelago’s main island, Heimaey. The volcanic fissure of this eruption in some places was only 200 meters from the nearest buildings. Not surprisingly, the eruption caused extensive damage in the town. 400 buildings were buried under a 6-meter layer of lava and pyroclastic materials. Many buildings burned to the ground, set on fire by the hot lava, and roofs collapsed in others covered by a particularly thick layer of tephra.

As the eruption happened in completely modern times, it has been documented, among other things, in many harrowing Photos. The Eldheimar Museum, also known as the Fire Museum, the Lava Museum or the Volcano Museum, brings visitors closer to this eruption and is a must-visit on a trip to “Vestmany” (see Vestmannaeyjar – islands off the south coast of Iceland).

Meradalir – latest popular eruption

On August 3, 2022, after several weeks of light tremors and a few days of very frequent and quite strong tremors, the Krýsuvík (Krýsuvík-Trölladyngja) volcanic system on the Reykjanes peninsula resumed its eruption for a couple of weeks. In 2021, it created an extremely spectacular and popular crater in the Geldingadalir valley, on the slopes of the Fagradalsfjall mountain. The 2022 eruption, on the other hand, was fissure-like and run through the neighboring valley, Meradalir.

On August 3, 2022, after several weeks of light tremors and a few days of very frequent and quite strong tremors, the Krýsuvík (Krýsuvík-Trölladyngja) volcanic system on the Reykjanes peninsula resumed its eruption for a couple of weeks. In 2021, it created an extremely spectacular and popular crater in the Geldingadalir valley, on the slopes of the Fagradalsfjall mountain. The 2022 eruption, on the other hand, was fissure-like and run through the neighboring valley, Meradalir.

The 2022 eruption was stronger than the 2021 one, but lasted for only 3 weeks (vs 6 months in 2021).It was also located a bit further from roads and parking lots, so the walking route to it was about 1.5 km longer.

Due to the nonetheless fairly easy access and the gentle course, the eruption from the site had again become a huge tourist attraction. After all, we rarely have the opportunity to see the fresh lava flowing from the volcano up close, moreover, without having to travel to the other side of the world. Meradalir Valley is located about 20 kilometers southeast of Keflavik International Airport, about 30 kilometers southwest of downtown Reykjavik and only about 10 kilometers east of the popular Blue Lagoon Spa. The walking route from the nearest parking lot is about 6 km one way.

The 2022 eruption, like the 2021 one, was one of the small and quiet ones, but that’s why it was relatively unthreatening and you could see it up close with your own eyes in relative safety. No wonder it attracted many tourists and was a huge attraction for native Icelanders as well.

Read more about that eruption in a separate article: Iceland’s newest attraction – the Meradalir eruption.

Bibliography

- Gudmundsson, Magnus & Larsen, Guðrún & Hoskuldsson, Armann & Gylfason, Ágúst. (2008). Volcanic hazards in Iceland. Jökull. 58.

- Thordarson, Thorvaldur & Self, S. (1993). The Laki (Skaftdr Fires) and Grimsvotn eruptions in 1783-1785 Bulletin of Volcanology. 55. 233-263. 10.1007/BF00624353.

- Thordarson, Thorvaldur & Larsen, G.. (2007). Volcanism in Iceland in historical time: Volcano types, eruption styles and eruptive history Journal of Geodynamics – J GEODYNAMICS. 43. 118-152. 10.1016/j.jog.2006.09.005.

- Newhall, Chris & Self, Stephen. (1982). The Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI): An Estimate of Explosive Magnitude for Historical Volcanism Journal of Geophysical Research. 87. 1231-1238. 10.1029/JC087iC02p01231.

- Fraedrich, Wolfgang & Heidari, Neli. (2019). Geology of Iceland 10.1007/978-3-319-90863-2_4.

- A. R. Schmitt and A. Kuenz, “A reanalysis of aviation effects from volcano eruption of Eyjafjallajökull in 2010,” 2015 IEEE/AIAA 34th Digital Avionics Systems Conference (DASC), Prague, Czech Republic, 2015, pp. 1B3-1-1B3-7, doi: 10.1109/DASC.2015.7311335.

- Oppenheimer, C., Orchard, A., Stoffel, M. et al. The Eldgjá eruption: timing, long-range impacts and influence on the Christianisation of Iceland Climatic Change 147, 369-381 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-018-2171-9

- Icelandic Met Office, Catalogue of Icelandic Volcanoes, https://icelandicvolcanoes.is/

- Global Volcanism Program, Smithsonian Institution, https://volcano.si.edu/

- K. Gronvold, Myvatn fires 1724-1729. Chemical composition of the lava Nordic Volanological Institute 8401, University of Iceland, Reykjavik 1984.