T

he best time to visit Ytri Tunga is early summer (June-July). The viewing itself is relatively pleasant then, and there may be many newborn common seal pups in the herds (they are born in May and June).

Ytri Tunga is a beach located at the farm of the same name on the Snaefellsnes peninsula. Ytri Tunga beach boasts beautiful golden sand, but that’s not what makes it popular.

Ytri Tunga is probably the best place in Iceland for watching seals. Just off the shore, on the rocks rising out of the water practically all year round, you can see at least a few individuals from the local colony.

While on the beach, look around – the seals do not have to lie right in front of the parking lot 🙂 Both on the left and right, there are promontories about 100 meters away, from which you can see them better (binoculars will come handy).

If the tide is out and you’re not afraid to climb the rocks, you can see the seals really close up. However, do not come too close so as not to scare them off. When observing seals, keep at least 50 meters away from the nearest one. A seal on land won’t catch up with you, of course, but you’ll scare it off by getting closer and it will run away from you into the water.

T

TIf you are watching juveniles, the recommended distance is 100 meters. When seals make sounds or alarm signals or move around, it may mean that they are disturbed. If this happens, step back and give them enough space so that they feel comfortable again. Also, never stand between a seal and the ocean shore. It’s very important for seals to have easy access to the water. It makes them feel safe.

Other good places to see seals in Iceland include the Jökulsárlón lagoon in the South and the Vatnsnes peninsula in the North. You are more likely to see seals from afar there, but on Vatnsnes you may be lucky to see a large herd basking on the beach….

On Ytri Tunga, first of all, you will see the most popular species in Iceland – common seal (Phoca vitulina, also called harbor seal). The much larger gray seal (Halichoerus grypus) also comes here, but less often. These two species are certainly the most common seals found in Iceland, although Greenland ice seals (Pagophilus groenlandicus), ringed nerpas (Phoca hispida), sea hooded seals (Cystophora cristata) and bearded seals (Erignathus barbatus) can also be spotted here.

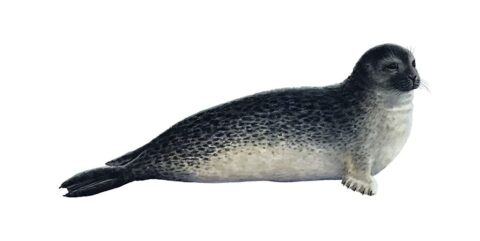

The common seal is the most common seal species in Icelandic waters. It is much smaller than the gray seal, and distinguished by its shorter snout. Male and female common seals differ only slightly in size. The male weighs an average of 100 kg (220 lbs) and is slightly heavier than the female, whose weight averages up to 90 kg (ca. 200 lbs). The body length of the male and female common seal is about 1.7 m (5’7″) and 1.6 m (5’3″), respectively. Different coloration is observed depending on the season, as well as the sex and age of the animal. Female common seals live longer than males, living to more than 30 years.

Common seal

Common seal is a herd species and can often be found in clusters on the ocean shore, although this is rare in winter. In spring, females gather in colonies on land to give birth to offspring (May-June), usually one young each. The lactation period lasts 4-6 weeks. Colonies are believed to be a way to protect themselves from predators. In early summer, males appear in the colony. During the heat period, they compete for access to females and attract them with various gestures. The winning dominant males will have the opportunity to copulate with multiple females, and the young will be born the following spring. During the winter, males and females rarely stay together, while young individuals are rarely with the older ones.

Historically, the common seal was a more common species in Iceland. In 1972-78, the population of these animals in Iceland was estimated at 43,000 individuals. However, in 2006 and 2011, the number dropped to 12,000. After counting individuals in 2014, it turned out that there were only about 4,000. These results suggest that the common seal population has declined by more than 90% over the past 40 years.

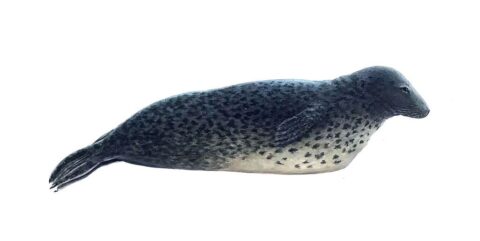

The gray seal is much larger than the common seal. Males can weigh up to three times as much. They have rather large and wide heads, with an elongated snout. Male and female gray seals clearly differ in size: males average 280 kg (over 600 lbs) in weight and 2.4 m (7’10”) in length (and the largest individuals can weigh as much as 300 kg and measure 3 m). Females average 165 kg (360 lbs) in weight and 2 m (6’6″)in length. Their coloration is gray or dark gray, varying depending on sex and age of the animal. Gray seal pups come into the world covered with dense, soft, silky white “baby” fur, which is replaced after 3-4 weeks by waterproof fur. Like the common seal, female gray seals live longer than males and reach at least 45 years of age.

Gray seal

As with common seals, male gray seals copulate with multiple females. After the birth of the young in autumn (September-November), the lactation period lasts about 2 weeks for females. Males defend the area where females with pups are located. The mating period begins as soon as the females reach readiness, that is, at the time of weaning the young. The strongest males defend the most attractive breeding sites. During this period, females are sometimes aggressive, and so gray seal colonies are often smaller than those of common seals. Where there are fewer females it happens that the male defends only one female partner. However, during the moulting season, these animals often cluster together in large groups. Outside of mating and moulting periods, they live mostly solitary.

The population of the gray seal in Icelandic waters has long been much smaller than that of the common seal. In 1982 it was estimated at 10,000 individuals, and in 1990 at 12,000. In 2002 the population of the gray seal declined to 5,000, and in 2012 to 4,000 individuals. This means that between 1990 and 2012, the abundance of this species in Iceland decreased by 67%.

In the past, seals were extremely valuable to the people of Iceland, and in difficult times, they were a key factor for survival. Seal meat was eaten, the oil from their fat was used as fuel for lighting, and, of course, the skins were used for clothing and shoes. Seal fur was also a valuable export product.

Economic development, however, meant that seal hunting was no longer a necessity. Thanks to protests against the killing of seals in Canada, Russia and Norway, the commercial market collapsed around 1980. Since then, Icelandic seals also no longer need to be afraid of humans (although hunting in certain specific situations is still allowed). Unfortunately, despite this, seal numbers have recently declined – most likely due to a change in environmental conditions.

Ytri Tunga is located roughly in the middle of the Snaefellsnes Peninsula, on its southern coast, just off road 54, about 20 km west of the junction with road 56. From road 56, turn south at a small sign pointing to Ytri Tunga beach. Here there is a parking lot, an information sign and a small path to the beach.

It’s about 35 km (22 mi) east from Arnarstapi, and about 160 km (100 mi) northwest from Reykjavik. Ytri Tunga can be the first (or last) stop when visiting Snӕfellsnes.