Po beyond the “big three”(Laugavegur, Fimmvorduhals and Hellismannaleid), getting to the trails usually requires your own car.

What you can count on and what to expect on Laugavegur and other Icelandic trails. How to prepare for such a trip and how to organize it. Where to go and what to visit.

Most tourists get to know Iceland by driving around by car. This way you can relatively quickly see all, or almost all, of the island’s attractions. However, the real face of Iceland is not the crowded parking lots at the largest waterfalls. Most of the area of this beautiful island is empty, post-volcanic expanses, where it is much easier to meet a sheep than a human being. It is very worth seeing this side of Iceland as well, but for this purpose you need to go on a full-day or better: several days hiking trip.

Iceland’s most famous hiking trails

There are plenty of mountain huts, hiking huts and campgrounds in Iceland. And between them there are many hiking trails. The most famous multi-day trail is certainly Laugavegur, connecting Landmannalaugar and Thorsmork. Two other trails connect to it: Fimmvorduhals and Hellismannaleid. In total, it is possible to hike on these trails for up to more than 10 days, without descending to ‘real civilization’. Descriptions of these trails can be found in the linked articles. Less well-known, but also very interesting multi-day trails are set in the Kerlingarfjoll region and in the vicinity of the Askja volcano(https://www.ffa.is/en/the-askja-trail). But these types of multi-day trails are almost everywhere in Iceland. A beautiful few days of hiking is also provided by the Hornstrandir reserve in the far north, which is difficult to access. Finally, the most interesting routes for one day, sometimes not the whole day, are certainly a trip to Glymur waterfall, shorter routes in Landmannalaugar, Thorsmork and Kerlingarfjoll, an ascent of Mt. Esja, near Reykjavik, and several trails in Skaftafell reserve, on the southern coast. A specific and very interesting route is the walk to the hot mountain stream of Reykjadalur, above the village of Hveragerði. Both short and longer routes are worth weaving into the itinerary of a trip to Iceland. Passing the “set” Laugavegur + Fimmvorduhals + Hellismannaleid probably requires a separate trip, but the other routes can complement any summer trip. All these routes have many elements in common, or very similar. And you should prepare for all of them in a fairly similar way.

When to go trekking in Iceland

In Iceland, strictly speaking, there is no such thing as a mountain trail closure. The trail may be unsafe (e.g., snowy), shelters and campsites along its route may be closed, but there is no formal ban on entering them even in the middle of winter.

But, of course, trails are difficult to access in winter, and help may take a very long time to arrive if needed. Therefore, if you are not a fan of winter hiking, it is certainly best to go there in the summer – indicatively, this is the period from mid-June to mid-September, with July being the most convenient for sure. For those going on multi-day trips from Landmannalaugar and Thorsmork, the essential season is from mid-June to mid-September. That’s when hostels, campsites and stores are open there, and that’s when you can get there comfortably by bus. On the other routes it is similar, but perhaps there are not so many facilities (stores, buses) and such a big difference between the number of tourists in and out of season. In July – compared to other months – Iceland is the warmest, least rainy and least windy. Of course, while we can realistically count on rain-free weather then, the lack of wind would be a complete rarity, as would temperatures above 25 ºC. Regardless of the season, Iceland is still a fairly cool and windy island. In addition, the mountain trails, of course, are in the mountains, so temperatures there are lower and the wind is stronger than in Reykjavik, for example. June and July also have the longest days – even more than 20 hours pass from sunrise to sunset

We write much more extensively about the weather in Iceland in the article Weather in Iceland – temperature, wind, precipitation and encourage you to read it. Here we will only mention that even in summer, you can count on daytime temperatures above 15 ºC, but rather not above 20 ºC. So compared to Poland, this is rather spring weather, and not from some particularly warm spring. The situation is more serious if you go to the mountains and want to sleep in a tent. In the interiors and highlands, even in July (and this is the warmest month), temperatures at night can drop below zero (see the article Weather in different regions of Iceland). There can always be even a frost, and temperatures below 10 ºC are a complete standard. We don’t have ground temperature data from the meteo stations in the interiors, but the graph above shows that more than half of the July nights in Reykjavik pass with ground temperatures between 3 ºC and 9 ºC, and almost 10% of those nights record temperatures below 0 ºC. And yet, temperatures in the interiors (see article on weather in different regions), are about 2 ºC, to as much as 5 ºC lower than in Reykjavik. So when planning to sleep in a tent in the interiors, you need to be ready for temperatures around zero or even lower.Access to hiking routes

Commutes are, unfortunately, quite a hindrance to the organization of hiking tours and therefore largely define the shape of the entire trip

The multi-day trails from Landmannalaugar and Thorsmork are best accessed by bus from Reykjavik. We can then get to the start, and after a few days take a return bus at the other end of the trail. We write about this in more detail in the aforementioned articles on Laugavegur, Fimmvorduhals and Hellismannaleid, respectively. It’s a good idea here to spend the night at the Laugardalur campsite in Reykjavik (or at the Dalur hostel there), as there is a bus stop right next to it from which these buses depart. Alternatively, quite a few people arriving in Iceland at night choose to spend the remaining few night hours at the BSI station – another bus stop. The station doesn’t open until 3 a.m., but a small vestibule is open 24 hours a day. There’s also a luggage storage facility, and at the nearby N1 station you can buy, among other things, gas for your kettle. This is a sensible choice, because when going to the mountains you probably have a carrimat and sleeping bag with you anyway, so you can nap quite comfortably at the station.Po beyond the “big three”(Laugavegur, Fimmvorduhals and Hellismannaleid), getting to the trails usually requires your own car.

For the other trails, it’s a bit different. We basically have to get to Glymur by our own car (or possibly by hitchhiking). Likewise to Kerlingarfjoll, but here we need a 4×4 car. By city bus we can get to trips near Reykjavik: to the small Úlfarsfell hill (lines 18 and 104, stop Skyggnisbraut) and the already quite large Esja (line 29, stop Esjuraetur).

By long-distance bus we can reach Skaftafell (line 51). Toward Askja we can get to Myvatn (57 to Akureyri and then 56), but the last 100 kilometers from the vicinity of Myvatn to the volcano itself have to be covered by foot, tour bus or on foot. On the other hand, we will reach Horstrandir only by ferry from Isafjordur, to which, unfortunately, buses (also) do not run.

Standard of Icelandic hostels and campsites

Writing about Icelandic campsites, one fundamental caveat must be made: campsites in the lowlands (including, in particular, those along Highway 1) and campsites in the interiors are two different worlds. Campgrounds, hostels and lodges in the lowlands offer practically everything. Fully equipped kitchens, unlimited electricity, hot water, trash cans, wifi – all these are taken for granted as standard and naturally mandatory things

Meanwhile, mountain huts – and even more so campgrounds in the interiors – often offer only very basic comforts. And those staying overnight at a campsite do not have access to the shelter at all, and therefore cannot use the kitchen, canteen or drying room in the hut.Shelters, of course, offer protection from wind, rain and cold, but in many of them sanitary facilities are outside. So if we want to take a shower, we have to deal with the current aura (also because there is usually a line to the showers). At Laugavegur, each campsite also runs a small store, but on other trails this is rather rare.At Landmannalaugar we have a hot spring, as do, for example, those at Laugafell, Laugarfell and Hveravellir huts. In Kerlingarfjoll to the spring from the campsite is approx. 1.5 km.

Video: hot spring in Landmannalaugar

With few exceptions (e.g. Laugarfell, Fimmvorduskali) it is also possible to pitch a tent at each hut or shelter. Then we can not use the hut kitchen, but we can use the sanitary facilities (which, however, does not always mean, for example, a shower). Most campsites in the interiors are poorly sheltered from the wind. Also, comfortable, soft, flat grass is rather rare on them. So when pitching a tent, you have to reckon with difficult, hard ground and support the tension of the lines with rocks (which – fortunately – are usually in abundance). As a rule, there is also no access to electricity in hostels and campsites. Sometimes charging your phone is possible for a fee, and sometimes it requires ‘begging’ the person running the campsite. But most often it is simply impossible. Especially hard-to-reach hostels and campsites also do not allow you to leave garbage. Sometimes they make an exception for aluminum cans and plastic bottles, but most of the trash we have to take with us and throw away at the next stop. Such places include Baldvinsskali, Hrafntinnusker and Emstrur-Botnar

There are special “exchange shelves” at many campgrounds. There we can leave food or equipment that we no longer need, or look among them for something we are missing. Realistically, we can count on this in places where tourists finish their trips – such as campsites in Thorsmork and Grindavik. On the other hand, the exchange shelf in Landmannalaugar usually shines empty… Certainly, you will find the most free stuff at the campground in Reykjavik (Laugardalur). Often something valuable can also be obtained from camper rentals. You won’t get free provisions for days this way, but some tea, pasta, jam, sugar, salt or dishwashing liquid – as much as possible. Everywhere you can pay for everything by credit card. Even if the campsite still has a coin-operated shower (such as Rjupnavellir or Emstrur-Botnar), we don’t need to bring coins with us – we’ll get them at the reception in exchange for a corresponding charge on the card.Necessary fitness preparation

It is difficult to compare the difficulty of Icelandic trails with those in Poland or other European countries.

Iceland’s highest peak is Hvannadalshnúkur, which reaches as high as 2110 meters above sea level, but Icelandic trails rarely climb above 1000 meters above sea level. So it’s not high, although due to its location close to the Arctic Circle, we can already successfully encounter year-round snow at such an altitude. However, even if there is snow, most of the trails in Iceland are typically lowland in nature. We walk on relatively flat and clear paths

Only in the really most difficult places do the trails get steep and – often – loose. The trails in such places are sometimes secured with ropes and – less often – chains, but unfortunately these ropes and chains are also not very well maintained. Sometimes they are attached to the rock quite loosely and do not give a sense of security. So you have to be careful, because it is not difficult to have an accident.Short trails – several hours long

Short trails are usually a maximum of a few hours of hiking. The aforementioned trail to Glymur waterfall is a total of about 10 GOT round trip (6.5 km), so the route for 3 hours, maximum 4 (1 GOT point is 1 km on the flat or 100 m “up”). The loop to Svartifoss, is less than 6 GOT (4 km), or up to 2 hours of walking. From the parking lot at Skogafoss, you can climb Fimmvorduhals as far as you feel like and come back. It is worth going up there even 2-3 hours, but the first beautiful viewpoints are encountered there after less than an hour of walking. The small Tindfjoll loop from Langidalur campground is about 9 GOT, or 2-3 hours of walking, and the large one is about 13 GOT, or about 4 hours. In Landmannalaugar, the loop from the campsite through Blahnukur and Brennisteinsalda is a total of about 15 GOT, or 4-5 hours of walking. So all of these are short trails. The kind for which we pack and dress just before going out, for which we don’t need to take food, and for which we only need water, and for which we are unlikely to go if it is raining or there is a hurricane wind. That’s why we don’t need any special preparation for them. Multi-day trails certainly require more attention.Multi-day trails

Hostels and campsites on multi-day trails in Iceland usually lie no more than 20 km from each other and 20-25 GOT points. At the same time, they also rather rarely lie closer to each other than approx. 15 km / GOT. Therefore, when planning routes, we have to decide either on a rather lazy 20-25 GOT per day, or on an already very strong 40-50 GOT.

At a standard pace of about 4 GOT per hour, this gives us daily stretches of 5-6 hours or 10-12. In summer, a day in Iceland is long (even lasts more than 20 hours), but still, 12 hours of walking per day (usually with a heavy backpack), is really a lot, so most hikers, however, walk at this leisurely pace of about 20 GOT/day. For comparison, here are some examples of trails of about 22 GOT in the Polish mountains:

- Bieszczady: ascent to Tarnica from Muczne and descent to Wolosaty;

- Beskid Zywiecki: crossing from Zawoja (stop Zawoja Markowa), to Babia Gora and descending to Krowiarki Pass;

- Gorce: loop from the Kowaniec Pętla stop, to the Turbacz mountain shelter and back;

- Karkonosze: ascent from Karpacz (Kopa stop) to Śnieżka via the black trail and return via the red trail;

If you can walk these types of trails, you are able to walk the vast majority of trails in Iceland. So it is not very demanding in terms of fitness….

Pamiętaj that on the longer trails you will go with a heavy backpack, in potentially bad weather conditions and in a series of several days, sleeping in a tent or in simple shelters, which increases the level of fatigue perfectly. It’s not good to demonize or fear Iceland, but it’s not good to underestimate it either 🙂

Equipment: what to bring with you

Mountain tours in Iceland require basically the same equipment and preparation as anywhere else in the world, although they certainly have their own peculiarities as well. These peculiarities are firstly due to the fact that the weather here is usually spring-like at best, and the fact that it’s practically always blowing really hard.

Video: What equipment to take on a trek in Iceland

If you plan to explore Iceland by car and only go out into the mountains for a maximum of a few hours of trails (e.g. Glymur), then you don’t need to take any particularly professional equipment. After all, if the weather is really bad, you’ll probably abandon the trip anyway. And if, for example, the rain “catches” you on the trail, you’ll still dry off the same day in the evening. The situation is completely different if you go to the mountains for several – or a dozen – days….

Shoes and other walking gear

What shoes to take to Iceland? On a ‘car’ trip, the so-called approach shoes will work best. But on a multi-day trekking trip, a good pair of high mountain boots will certainly come in handy. Although you can even see people on the trails in holey (sic!) ordinary sports shoes, but we recommend tough and waterproof high ankle boots.

Approaches are shoes that look like typical mountain boots, but “cut off” below the ankle (in the video below: red shoes in the middle). They are stiff boots, with a thick sole and a waterproof, durable upper, but short, so they are lighter and more comfortable than “full” mountain boots. They are also more convenient for transport. They are great for visiting the attractions of the Golden Circle or those along Highway 1, or for a short trip of a few hours, such as to the aforementioned Glymur waterfall.

Video: What shoes work best in Iceland (winter and summer)

However, Icelandic trails are sometimes – like probably all mountain trails – uneven and slippery (here: due to loose scree). Therefore, on longer, multi-day trails, tall mountain boots are best. They give extra protection against twisting or tweaking of the ankle, which becomes fundamental on a longer trip.

Such boots (and stomping boots!) will also come in handy because of their water resistance. On a multi-day tour, we can’t always wait out the rain, and while storms in Iceland are practically non-existent, a few hours or even a few days of drizzle is nothing strange. In addition, the ground on the trails is uneven, sometimes (even in summer) you have to walk through a patch of snow, and loose scree or volcanic cinders require you to drive your shoe harder into the ground. On the trails you can find hikers in a wide variety of footwear, but these are certainly the conditions for which hard, tall mountain boots were just made. If you have such or can afford to buy them, they will certainly be the best choice. In addition – on longer trips – water shoes will really come in handy. First of all, for crossing streams safely, comfortably and quickly (and therefore also comfortably). But such shoes are also useful as footwear for showers or hot springs

In winter, but in fact from October even to April-May, crampons can come in handy as much as possible. Not full, ice crampons, but small metal teeth stretched on small chains and attached to the shoe with the appropriate rubber – crampons. This is a sensational solution. In summer they are unlikely to come in handy, but in winter they can be absolutely essential for many walks, even short and typically hiking ones(Gullfoss, Seljalandsfoss, many others). Certainly, all year round trekking poles are also useful. Due to the aforementioned scree (sometimes steep) and the need to cross streams, poles will come in handy on most trails.Other than that, normal equipment for mountain hiking is necessary. A rainproof (so-called hardshell) and windproof jacket (and pants), thermal underwear, good socks, warm fleece. Gloves and a hat in winter, or at least autumn, are also sure to come in handy, even in summer

A backpack is also necessary, of course, but I guess all the brand-name backpacks offered nowadays are really good. Although – in my opinion – almost the largest capacity currently available, i.e. 75 liters, is the absolute minimum for a longer trip. Although, as I describe a little further on, I usually hike with a really big sleeping bag and an equally big tent. For shorter trips (less food!) and with a smaller sleeping bag, perhaps a 65 liter backpack would also suffice. It is worth making sure that the harness attachment system will not pinch your back. Unfortunately, this is not out of the question – systems based on a large, plastic plate as a harness attachment, unfortunately, can pinch Pay attention to the length and positioning of the side straps. If you plan to carry, for example, a carrimat and a tent clipped to the sides of the backpack, these trocars really should be as long as possible. On the other hand, for example, large additional side pockets will interfere with this. Also remember about the rain cover. If your backpack doesn’t have such a cover integrated, it’s essential to buy a universal one of the right size. Appropriate – i.e., taking into account, for example, a tent or a carrimat attached to the sides of the backpack, not just the backpack itself If you’re traveling alone, it’s definitely worth taking a satellite communicator (such as the Garmin InReach Mini) with you. It reads your position from the GPS, allows you to transfer the data later to your phone or computer, but most importantly, it allows you to call for help via the satellite network. If you have an accident that makes it impossible to continue walking on your own, the ability to call for help from any point along the route (and off-trail, if you lose the trail), is absolutely priceless. In the lowlands we have GSM coverage virtually everywhere, so a phone should be enough to call for help, but in the interiors, by contrast, GSM coverage is almost nowhere, so satellite communication is really helpful.Remember that there is also no electricity in the interiors, so we can’t really rely on devices that require daily charging. And on the other hand, that you absolutely need to take with you as large a power bank as possible, because a smartphone is extremely useful on the trail these days. If you use your phone only for navigation and payments, that is, constantly in airplane mode, and don’t take very many photos and videos, a 10,000 mAh powerbank should easily last you up to 10 days

It’s definitely worth taking sunscreen to Iceland. The weather is usually cool and the sun doesn’t rise very high. But when the day is cloudless, there is absolutely nowhere to hide in the shade on Icelandic trails. Your face, neck, hands and other uncovered parts of your body will be in the sun all the time, and after a day or two, this can be a serious problem. If being bitten by midges or mosquitoes is an unbearable thing for you (or you are allergic to them), then also take along a cream to soothe the bites. Nuisance clouds of midges are not standard, but they do happen nonetheless, especially on larger lakes and in windless weather. Fortunately, fighting midges is one of the (few) advantages of the constant, fairly strong wind in Iceland. Sometimes a face scarf, bandana or buff / buff is also useful. Due to its volcanic structure, Icelandic trails often run through fields of volcanic ash and cinders. And when a strong wind blows in such a place, we can find ourselves in the middle of a sandstorm of sorts. Taking goggles would be overkill, but a buff helps then to breathe calmly.Tent, sleeping bag – sleeping gear

What kind of sleeping bag to take to Iceland

If you’re sleeping in a tent, it’s best to equip yourself with a sleeping bag with comfort down to 0 ºC. Of course, you are likely to spend many nights rather in temperatures around 8 – 10 ºC, but it is worth preparing for those colder times.I myself use an anilan sleeping bag several years old with a nominal comfort of -1 ºC, because that’s just what I have. Of course, thermal comfort at night is influenced by many factors, but – even though I’m an 80-pound “seasoned” guy – some nights at campsites – even in July – are cold enough that I have to dress extra in such a sleeping bag.

Of course, a newer sleeping bag would probably be warmer, and a down sleeping bag would be much lighter and smaller. But also much more expensive. That’s why, since I already have such a big ‘anilanka’, that’s what I use, even though for me the minimum comfort temperature in this sleeping bag is more like about 5 ºC. If you sleep in huts, take a spring sleeping bag – one with a comfort temperature of about 10 ºC. Although in huts it is usually warmer (sometimes even hot), but it is not uncommon to sleep with the windows open, so the temperature in the room is not ‘roomy’. Of course, in contrast, some huts are just hot at night, but getting out of the sleeping bag is, after all, quite easy, and getting warm on a cold night is much more difficult.

What kind of tent will work in Iceland

Because of the low temperatures and wind, it would be good for your tent to have a tropic that goes all the way down to the ground and a relatively warm bedroom.

Nowadays, virtually all tent bedrooms are very airy (“superbly ventilated”) and act as mosquito nets rather than protection against cold and wind. On the other hand, from the perspective of Iceland, the best would be a tent in which the mesh part of the bedroom walls started as high as possible. The tent whose bedroom can be seen in the photo below is not good for Iceland. Unfortunately, in the part where the mesh begins at the very floor of the tent, the wind penetrates the interior without any problem, making it noticeably windy and just plain chilly inside.

On the other hand, the tracker and the entire structure of the tent should be resistant to rain falling in strong winds. Certainly igloo tents work well here, especially those in all-season or “three-season” specifications. It doesn’t have to be a typical winter tent, because we don’t even need snow aprons. On the other hand, in classic tents, well-placed lashings are very important – so that the side wall of the tropical under wind pressure cannot touch the bedroom.

It must be said that ultra-light tents are increasingly popular on the trail. Usually single-layered, with the bedroom acting only as a mosquito net, and not any protection from wind or cold. Such a tent basically consists of sheaths alone, as it is pitched on a trekking pole (or two) acting as a mast.

The main advantage of these tents is their small size and even negligible weight. According to tourists we met on the trail, their 2-person ultra-light tents weighed as little as 0.5 kg. So compared to our 3-person igloo weighing about 4.5 kg, the difference is colossal. Of course, such an ultra-light tent is also small. That’s good, because it takes up little space in a backpack, but bad, because it’s hard to fit a backpack inside, at night, and it’s also quite a challenge to even change inside in the rain, without touching the tropics. Igloo, however, is much more spacious. At the same time, manufacturers of ultra-light tents assure that they can withstand strong wind (and rain) due to special shapes, etc. However, almost all the “tents in trouble” videos you can find on the Internet are just tents with a classic, masted design, so it’s probably safer to stay with the igloo.

If you’re traveling around Iceland by car and carrying a tent in the trunk, a large igloo is the obvious choice. Icelanders even bring tents to campgrounds where they could comfortably park their car (seriously-seriously!). However, if the tent has to be carried on the back, the choice is more difficult.

The ultra-light tent is, of course, tiny and lightweight, but also unfortunately expensive. And frankly, having seen several such tents at campgrounds, I am not convinced by the assurances of their manufacturers about high resistance to strong winds. In contrast, an igloo (or tunnel) tent, especially in the winter version, will be heavy, but spacious and relatively cheap. Which of these things is more important – everyone must decide for themselves here.

Accessories and extras

Low night temperatures and (at many campsites) hard, cinder-block ground encourage sleeping on a hiking mattress or a self-inflating mat. Unfortunately, again: mats that are lightweight and durable will be expensive, and those that are cheap tend to be quite heavy (or not very durable). In terms of equipment carried in a backpack, I am a firm opponent of any pumps. On the other hand, a cool solution is mats inflated with a kind of cushion. Such a bag is easily filled with wind, and then its contents are forced into the mattress. The system is very comfortable and lightweight. And at the same time, after removing the air, it takes up very little space in the backpack. Unfortunately, if it is also made of really durable materials, it is not one of the cheap solutions. Alternatively, as good as possible is also a “good old” karimata. Although the karimata is large and not very soft or comfortable, but it is very light and very cheap. And in addition, the puncture of even the biggest hole basically does not bother the karimata anything, while all inflatable mats, unfortunately, have to be patched when something happens to them. In Icelandic conditions, due to the low temperatures, it is definitely worth equipping yourself with a thicker, two- or three-layer mat.

Instead, we tested ordinary, flat carimata, compared to the more modern ‘egg crate’ (egg crate) type of carimata. And unfortunately, the extruded one turned out to be neither lighter, nor noticeably warmer or more comfortable, while it was completely impossible to cinch into a backpack from the side. The square cross-section when folded meant that it was a tad too big to be embraced by the backpack’s side straps. Usually this was not a problem, but when it started to rain and a cover had to be put on the backpack, there was absolutely nothing to do with this carimat…. Nevertheless, in general, at least judging by the Icelandic trails, karimats are definitely going out of use, in favor of lightweight inflatable mattresses. Of other things in the summer, it is really worth taking a sleeping band. It’s a type of blindfold, familiar from intercontinental flights, ensuring that you sleep in the dark, even though the Icelandic night is short and not very dark. The blindfold is lightweight and hassle-free, and you get used to sleeping in it very quickly. This is perhaps especially important for those planning to stay overnight in hostels, as there is no institution of curtains or drapes in Iceland. It gets bright in the bedrooms as soon as the sun rises, that is, in summer, as early as about 4 a.m… Those who need silence to sleep may also want to bring earplugs. After all, in hostels we sleep in large, multi-person rooms, where it is not difficult to find at least one snoring person. And tents are constantly rustling (or even making noise) due to the incessant wind. Indeed – while solitude can be found quite easily in Iceland, true silence is much more difficult to find here due to the wind.Cooking and eating equipment

If you travel around Iceland by car, you can buy food in supermarkets and have complete freedom of what to eat. Admittedly, a lot of things (meat!) are really expensive, but compared to the overall cost of the trip, acutely the extra cost of food is unlikely to be a significant budget item (unless you rely on eating in restaurants – that’s something else entirely). If you are interested in the details of what costs how much and where to shop, please see the article Shopping in Iceland: food prices and grocery store opening hours and the other: What to eat in Iceland – interesting dishes and prices in restaurants. Importantly: you will find drinkable water in every stream and at every campsite. It’s worth taking a bottle or bidon with you for the day, but they don’t have to be large. A 1.5L PET bottle works great (although it could easily be smaller, too) of sparkling water or other beverage bought before you set out on your trip. Such bottles are very light, very sturdy and very easy to cuff to the outside of your backpack.

Given Iceland’s low temperatures and permanent wind chill, a small thermos is also useful. It doesn’t have to be big, especially since it’s better to keep it inside the backpack anyway. Thermoses kept outside the backpack cooled down surprisingly quickly for us in the relentless Icelandic wind.

Cooking under a tent

If you carry food with you in a backpack, freeze-dried meals are certainly best.Such dishes are small, light, really tasty and trivially easy to prepare. Their preparation takes a short time (so we save time and gas), but what’s more, a freeze-dried dish can be eaten straight from its package. So you don’t need to take an extra meniscus (or wash it) 🙂 Freeze-dried food is available in quite a wide range. Meat dishes are available, as well as vegetarian or vegan ones. You can also find breakfast dishes, as well as lunch or dinner dishes (large, double portions). Enough variety of the dishes themselves is available that our meals on the trip absolutely do not have to be monotonous. And they certainly don’t have to be so on a short trail of a few days

If necessary, we can replenish certain items of supplies at camping stores along the way, although this is more likely to be the case at shelters on Laugavegur or along larger roads (e.g., Nyjdalur). The usual items to buy are candy bars, chocolates, small sweets and a small selection of freeze-dried food or gas for stoves. The exception here is the store in Landmannalaugar, which offers a really wide selection of a variety of food and non-food items (more on that in a sub article about that campsite). Prices for the 2024 season at Ferðafélag Íslands (Icelandic Tourist Society) stores were announced back in October 2023. Of course, not all campsites and hostels belong to this society, but it’s a good indication of typical prices at campsites in the interiors. See our information on these prices here: [5.10.2023] New prices on the Laugavegur trail.Letting out a secret: freeze-dried meals (from the Feed the Viking series) cost 3,500 ISK, or a little over $110 apiece, at campsites. Therefore, even if the prices of ‘liof’ in Poland seem high to you, they are certainly not as high as in Iceland. If you sleep in a tent, you are not allowed in the hostel. You must bring your own kocherek, dishes and necessary cutlery. Once again: if you decide to eat only freeze-dried food, you will only need one pot in which to boil water (usually the one bought with the kocher) and literally one fork to prepare and eat the dish. Super simple, lightweight and efficient system 🙂

Some mountain campsites provide all guests with some old stable or barn for use as a canteen. At others there is a special garden tent serving such a role. But on some campsites there is nothing of the sort and we simply cook in front of the tent or against the wall of the hostel. Therefore, modern cookers with a sheltered burner, preferably incandescent, work very well. They are produced by Jetboil and MSR, but also by other companies. These designs firstly speed up the boiling of water itself, and secondly save gas, using much less of it “per session” Both of these features are very important, because firstly, we can’t always cook in a place sheltered from the wind (for example, in Afangagil or Alftavatn there is no such tent or room), and secondly, after all, we want to carry as little as possible on our backs. And these stoves, while slightly heavier than the ‘ultra light’ version, use much less gas. So the stove itself is heavier than the uncovered version, but we can take a smaller, and therefore lighter, container of gas, or the same container will last longer, so weight-wise we come out ‘zero’. Well, and what we gain is that the cooking itself really takes noticeably less time, so we also wait shorter for a well-deserved meal. In practice, it took us about 4 minutes to boil a liter of ice-cold water straight from the Icelandic tap. And the large gas cartridge (440 g) was enough to cook for 13 days, with about a week for 3 people and the second week for 2. In the end, we still had quite a bit of gas left over. I am convinced that for 2 people going for 10 days even just a small cartridge – one with about 220-250 g of gas – should be enough.Cooking in hostels

If you stay overnight in huts on the trail, you can use well-equipped kitchens.Admittedly, if you’re feeding on freeze-dried food, you’ll use practically only a kettle in the kitchen, but a variety of pots, pans, thermoses, plates, cups and a wide range of cutlery are available. Usually a grill is also available. So as much as possible, you can feed yourself in any way you choose.

Not all kitchens are as large as the one in the photo (that’s the kitchen, actually half of the kitchen in the Landmannalaugar hut). But even in the biggest ones it can sometimes be really crowded. Unfortunately, both breakfast and dinner everyone wants to eat at about the same time, so during these peak hours the hostel kitchens, regardless of their size, often prove to be too small. This, by the way, is another advantage or advantage of freeze-dried food, as boiling water is always available practically on hand.

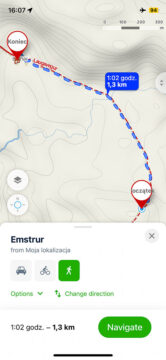

Useful apps and maps

Perhaps it’s a sign of the times, but nowadays in Iceland it’s quite fragile to have maps for hiking. Car maps are available as much as possible, but usually at a scale of 1:400,000, so they are completely useless for a hiker. Typical hiking maps are also available, but almost exclusively at a scale of 1:100,000. From the perspective of hiking trips, they do not allow for accurate navigation in more difficult areas, and are rather illustrative. The largest scale sometimes encountered is 1:50,000, and these are usually only selected parts of larger maps. Nowhere have we seen a map of a larger area at this scale. Neither in a bookstore, nor in any tourist store, nor from any tourist we met.

Only the most famous Laugavegur trail (and neighboring Fimmvorduhals, but no longer Hellismannaleid) “deserved” a special notebook edition of maps of the entire trail at a scale of 1:50,000. However, we saw this notebook on sale only at a stand at the BSI train station.

In addition, Icelandic trails often do not run along mountain ridges and valleys, and as much as possible they happen to cross flat, landmark-free post-volcanic plains. In such terrain, maps at a scale larger than 1:50,000 would be very useful for effective orientation, and even “the oldest Highlanders have not heard of such.”

I myself, out of habit, always take a printed map and compass with me, but in practice, walking on Icelandic trails, I have not taken them out of my backpack even once… It is also worth installing on your phone the safetravel.is app, which informs you about hazards and weather warnings. On this website, you can also register to receive such messages via SMS, during the selected period. The app also provides relatively good and ‘live’ information about volcanic eruptions, which, however, have recently been more of a tourist attraction than a threat (see: Iceland’s newest attraction – the Litli-Hrútur eruption). Finally, it is definitely worth having a local weather app – the one from vedur.is. The vedur.is website is run by the Iceland Met Office (Iceland Met Office / Veðurstofa Íslands) which is roughly equivalent to our IMGiW. It is certainly the most up-to-date and accurate weather data in Iceland. In winter, the service also gives a forecast for the occurrence of the aurora borealis. The other thing is that with the verifiability of these forecasts (both general and aurora) is really very, very poor.

There is no GSM coverageonmany trails in the interiors. So you won’t get an emergency SMS either. However, near campsites or on higher mountains or passes you sometimes manage to catch this coverage, so you can also check the weather forecast or news.

Travel insurance

There are (almost) no bans on entering dangerous places in Iceland, but there is also no free, state-run mountain rescue service like our GOPR. If we have an accident, we will have to pay (rather steeply) for any help we receive.Although with an EHIC card we (i.e. EU citizens) are entitled to the same free care in Iceland as Icelanders are entitled to, but unfortunately mountain medical transport and hospitalization is NOT free for Icelanders either. Then again, ordinary visits to doctors are not, either. We know of a case in 2023 where a tourist required transport from Laugavegur to the hospital and this transport alone cost him more than €2,000. The care and assistance provided at the hospital cost several times more. So, these are not cheap services. Therefore, in addition to getting an EHIC card (free), it is certainly worthwhile to purchase before the trip the appropriate insurance that includes an option to cover the cost of mountain rescue and possible medical assistance and hospitalization.

Compared to the cost of assistance on the spot, such insurance will cost pennies.