Representatives of 23 species of cetaceans can be observed off the coast of Iceland, of which at least 12 appear regularly in the area, while the remaining 11 species are observed occasionally.

Among the most frequent regulars are 5 species belonging to the whalebone (dwarf fins, blue fins, humpbacks, finwhales and seals) and 7 species of toothfish (bottlenose dhales, sperm whales, porpoises, grindwhales, orcas, white-beaked dolphins and white-sided dolphins). It is these species that we present more closely in this article.

Blue whale

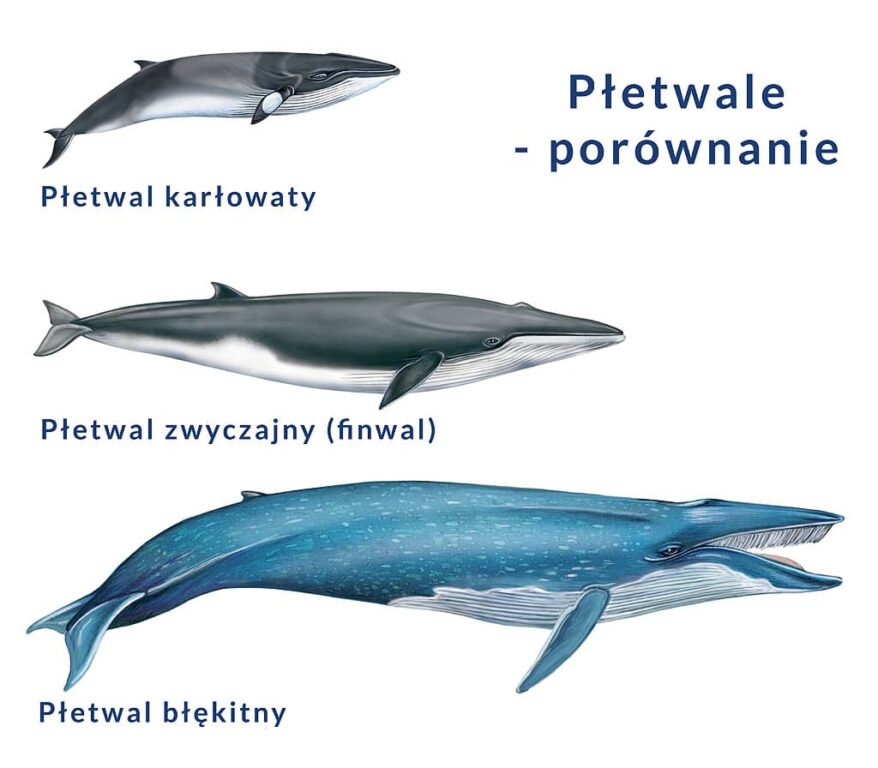

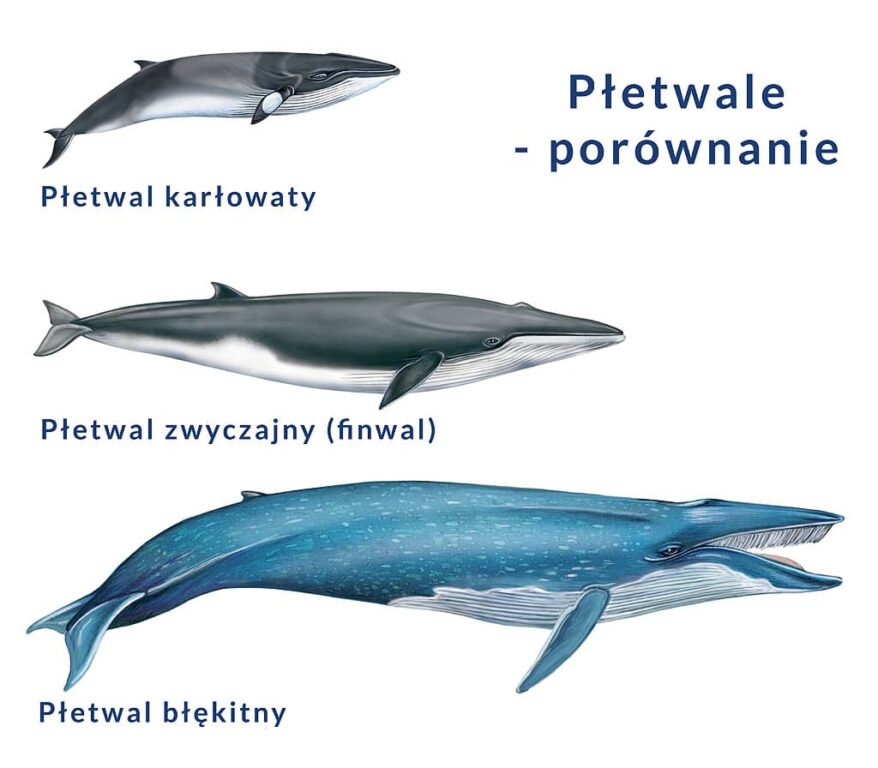

The blue whale (Lat. Balaenoptera musculus, Isl. Steypireyður, English: Blue whale) is a giant even among its whale relatives. It can reach body lengths of up to 30 meters and weigh more than 130 tons. It can travel at speeds of up to 50 km/h.

T

he blue whale is the largest animal that ever lived on earth It is both longer and heavier than the largest dinosaurs we know. Some dinosaurs, whose full skeletons have not been found (e.g. Argentinosaurus) and whose sizes we can only estimate, may have reached a greater total body length. However, they too were certainly lighter than the blue whale.

The main food of blue fins is krill, with occasional crayfish and fish. When cruising, they are most easily spotted thanks to their 9-meter tall air fountain. A characteristic feature by which you can also recognize a blue whale is its small dorsal fin, located at the back of the body. However, it must be admitted that unless you can get really close on a cruise, distinguishing between species is very difficult, and de facto you have to do it primarily on the basis of the size of the observed individual.

Comparison of features and sizes of 3 species of fins

Their considerable size and large amount of meat and fat caused blue whales to often fall prey to whalers, so their population declined sharply. They were only protected in the 1960s, and since then their numbers have slowly increased and stabilized. Nevertheless, they are classified as an endangered species, so they are under active protection. Their natural enemy is the plowshare, but it only threatens juveniles, older and weakened individuals.

Fin whale

Common fin whale (Lat. Balaenoptera physalus, Isl. Langreyður), is the second largest cetacean after the blue whale. It reaches lengths of up to 27 meters and weights up to 100 tons.

Common fin whale (Lat. Balaenoptera physalus, Isl. Langreyður), is the second largest cetacean after the blue whale. It reaches lengths of up to 27 meters and weights up to 100 tons.

The fin whale’s distinctive features are its pointed small dorsal fin and asymmetrical body coloration – the mandible on the left side is dark gray, almost black, while the right side is lighter, almost white. It is easy to spot in the environment, as the fountain of air blown by it reaches up to 5-9 meters in height.

According to the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature), it is classified as a species at risk of extinction, but has nevertheless been continuously caught off the coast of Iceland until recently. It is not a species often seen in these waters, but can be found during the summer months in both northern and southern Icelandic waters (Reeves et al, 2021).

Minke whale

Minke whales (Lat. Balaenoptera acutorostrata, Isl. Hrefna) are relatively small cetaceans. They reach a length of up to 10 meters and a body weight of up to 8 tons. They can swim at a speed of approx. 35 km/h. It is a species often observed during cruises, as it is curious, dives for short periods of time, and spends most of the day at the surface. It is most easily recognized by its small and curved dorsal fin and by the relatively small fountain of condensed air thrown up to 2 meters high. White bands on the pectoral fins are characteristic of this species.

Minke whales (Lat. Balaenoptera acutorostrata, Isl. Hrefna) are relatively small cetaceans. They reach a length of up to 10 meters and a body weight of up to 8 tons. They can swim at a speed of approx. 35 km/h. It is a species often observed during cruises, as it is curious, dives for short periods of time, and spends most of the day at the surface. It is most easily recognized by its small and curved dorsal fin and by the relatively small fountain of condensed air thrown up to 2 meters high. White bands on the pectoral fins are characteristic of this species.

There are 3 subpopulations of this species worldwide: one in the North Pacific, one in the Southern Hemisphere and one in the North Atlantic, visiting the waters around Iceland periodically. They usually move alone or in small flocks of 2-3 individuals. They can be observed in both northern and southern Icelandic waters.

They are among the most abundant whales in the oceans, but their population in Icelandic waters is declining year by year. This is due to climate change and their capture for human consumption. Their only natural enemy is the orca, which, however, mainly preys on young and weakened individuals.

Humbak

Oceanic longfinned whales, or humpback whales (Lat. Megaptera novaeangliae, Isl. Hnúfubakur), reach up to 17 meters in length and can weigh up to 30 tons. They can swim at speeds of up to 27 km/h and are known for their long migrations and spectacular acrobatic evolutions.

Oceanic longfinned whales, or humpback whales (Lat. Megaptera novaeangliae, Isl. Hnúfubakur), reach up to 17 meters in length and can weigh up to 30 tons. They can swim at speeds of up to 27 km/h and are known for their long migrations and spectacular acrobatic evolutions.

They are most easily recognized by their very long pectoral fins, which can reach a length of up to 1/3 the length of their entire body. These fins are equipped with special tabs that play a role in a specialized way of acquiring food. Group hunting by humpback whales is often observed, during which the pectoral fins increase the efficiency of food acquisition. Working together, the whales encircle a school of fish or zooplankton, disorient and stun them by striking their fins and leaping above the water. They also create a curtain of air bubbles, thus driving their victims into a deadly trap. They then rub at the shoal from below absorbing huge amounts of food and filtering it through the whalebone. Up to a dozen individuals can take part in such a highly effective hunt.

Humpback whales are also distinguished by characteristic nodules on the body, a small dorsal fin and an “S” shaped tail fin. Each individual has this fin individually colored which is a kind of whale fingerprint and makes it possible to distinguish individuals from each other.

Humpbacks are extremely curious animals and can often be found during whale-watching trips. Sometimes they emerge near the boat and follow it for a long time, which provides a great opportunity for observation.

Currently, their population is fairly stable, but this was not always the case. In the past, humpback whales were the main target of whalers from many parts of the world. Their penchant for shallow waters and seasonal return to the same areas contributed to this, making them an easy target. During the heyday of whaling, up to 95% of the world’s long-finned whale population died. A ban on hunting these animals was not introduced until 1966, when the population was in a deplorable state. Fortunately, it wasn’t too late, and today the species is no longer at risk of extinction, although it is still extremely important to keep the population in check (Mitchell and Reeves, 1983).

Sei whale

The sei whales, or melanoma fins, or seawals (Lat. Balaenoptera borealis, Isl. Sandreyður), rank a respectable third in size, thus closing the podium of the world’s largest cetaceans, behind the blue whale and fin whale. They reach lengths of up to 20 meters and can weigh up to 30 tons. They are among the fastest cetaceans, reaching speeds of up to 50 km/h (Horwood, 2009).

The sei whales, or melanoma fins, or seawals (Lat. Balaenoptera borealis, Isl. Sandreyður), rank a respectable third in size, thus closing the podium of the world’s largest cetaceans, behind the blue whale and fin whale. They reach lengths of up to 20 meters and can weigh up to 30 tons. They are among the fastest cetaceans, reaching speeds of up to 50 km/h (Horwood, 2009).

When cruising in Icelandic waters, you don’t see them very often as they tend to prefer open water and rarely approach boats. They can also be easily mistaken for finwhal. The main distinguishing feature between the two species is the fin whale’s asymmetrical coloration.

Like other species of cetaceans, the population of seals has been massively depleted due to whaling. Their meat was highly prized, and by the speeds they reached, they were considered difficult animals to hunt. Next to fin whales, they were the most frequently caught cetaceans in Iceland in the 1960s and 1970s. Red fins were only protected in the 1970s. Their population has still not reached adequate numbers, making them considered an endangered species and in need of active species protection.

Orca

The oceanic orca (Lat. Orcinus orca, Isl. Háhyrningur) is certainly the most predatory species, of all the cetaceans described here. Orcas are also the largest representatives of the Delphinidae (dolphinfish) family. They reach body lengths of up to 10 meters and weights of up to 9 tons. They achieve a considerable speed of movement (60km/h) by which they hunt very efficiently. Their diet includes fish, other dolphinfish, pinnipeds (including seals), as well as smaller and older cetaceans. They can be recognized by their long, pointed dorsal fin (can even measure more than 1.5 meters!), distinctive body coloration, and a large fountain of water, reaching a height of 4 meters.

The oceanic orca (Lat. Orcinus orca, Isl. Háhyrningur) is certainly the most predatory species, of all the cetaceans described here. Orcas are also the largest representatives of the Delphinidae (dolphinfish) family. They reach body lengths of up to 10 meters and weights of up to 9 tons. They achieve a considerable speed of movement (60km/h) by which they hunt very efficiently. Their diet includes fish, other dolphinfish, pinnipeds (including seals), as well as smaller and older cetaceans. They can be recognized by their long, pointed dorsal fin (can even measure more than 1.5 meters!), distinctive body coloration, and a large fountain of water, reaching a height of 4 meters.

Orcas are found in all oceans, but the highest abundance of these animals is observed in the North Atlantic (mainly just off the coast of Iceland and the Faroe Islands), in the North Pacific (mainly off Alaska) and off the coast of Antarctica.

The conservation status of orcas has not been clearly established, by insufficient information on the status of their populations. Individual populations are considered endangered, due to overfishing, pollution and habitat loss.

Sperm whale

Sperm whales (Lat. Physeter macrocephalus, Isl. Búrhvalur) are the largest cetaceans classified as toothfish. They reach lengths of up to 20 meters and can weigh 80 tons.

Sperm whales (Lat. Physeter macrocephalus, Isl. Búrhvalur) are the largest cetaceans classified as toothfish. They reach lengths of up to 20 meters and can weigh 80 tons.

Sperm whales are social animals, forming groups of about 12 individuals. They usually gather to protect young and sick members of the herd. They prefer open ocean waters. During the summer months, they can be observed off the coast of Iceland, but this requires luck and patience. This is because sperm whales hunt by diving as far as 1,500 meters, holding their breath for up to an hour. They feed mainly on squid and large fish.

We recognize sperm whales primarily by their characteristic fountain, thrown out at an angle at about 2 meters, through a single opening on the left side of the body. Other distinguishing features of sperm whales are a large head, specific ribbing on the back and a small dorsal fin.

In the chambers between the bones of the sperm whale’s skull is a special oily mass called spermaceti or olbrot. Adult individuals can accumulate up to 2,000 liters of this substance. It is involved in the production of peculiar “clicking” sounds for communication and echolocation, and also helps regulate buoyancy (Huggenberger et al., 2016). It was an extremely valuable resource, through which spermaceti were hunted en masse and their population was severely reduced. Spermaceti was used on a huge scale as a lubricant, raw material for candles, lamps, in the food and pharmaceutical industries. Spermaceti were also hunted for their specific digestive secretion – ambergris, which was used in the production of perfumes.

According to the Red List of Threatened Species, the sperm whale is at risk of extinction. The species is also on the CITES list, which means threatened with extinction. Fishing for this species is prohibited under the International Whaling Commission (88 member states).

Sperm whales are a very important link in food chains. Among other things, they are the main predator hunting giant squid. They eat huge quantities of these squid, thus having an impact on limiting their numbers. They also do the natural “recycling” involved in supplying iron to large, iron-poor areas of the ocean. The iron processed in this way is readily available to phytoplankton. The whole process is based on the fact that the sperm whale consuming fish and squid eating fish, which in turn feed on iron-rich zooplankton, contributes to the circulation of this element. Biochemical processes occurring during digestion change iron from an unabsorbable to a plant-available form. A similar system has been observed in the carbon cycle. The estimated contribution of the sperm whale to the conversion of carbon to its assimilable form allows for increased primary production and the fixation of an additional 200,000 tons of carbon per year.

Harbor porpoise

The harbor porpoise (Latin Phocoena phocoena, Isl. Hnísa), is a very common species in Icelandic waters. It is most often found during the summer months in bays and near shorelines. It feeds mainly on fish, which it sometimes hunts in larger flocks.

The harbor porpoise (Latin Phocoena phocoena, Isl. Hnísa), is a very common species in Icelandic waters. It is most often found during the summer months in bays and near shorelines. It feeds mainly on fish, which it sometimes hunts in larger flocks.

Despite its prevalence, porpoises, as one of the smallest representatives of cetaceans (it grows to about 2 meters and 70 kg), are quite difficult to observe in the wild. It swims rather alone, or in small groups of a few individuals. It rather rarely approaches boats and is hard to spot if the water is rough or visibility is poor.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature classifies this species as a species of least concern, meaning its global population is not threatened. However, in Poland, for example, the Baltic subpopulation is considered critically endangered.

Long-finned pilot whale

Long-finned pilot whales (Lat. Globicephala melas, Isl. Grindhvalur) grow up to about 6 meters and can weigh just over 2 tons. Females, however, are lighter and smaller.

Long-finned pilot whales (Lat. Globicephala melas, Isl. Grindhvalur) grow up to about 6 meters and can weigh just over 2 tons. Females, however, are lighter and smaller.

These whales are very often seen on cruises around Iceland, especially during the summer months. They form groups of 10-50 individuals, although gatherings of up to 1,000 individuals have been encountered. They have very strongly developed social bonds. In winter they tend to stay farther from the shores, while during summer and autumn they stay closer to the coast, making them grateful objects of observation. Juveniles often jump out of the water, which makes quite an impression.

Due to its social behavior, the species is particularly vulnerable during hunting. In many countries, these animals are still traditionally harvested and have not been officially covered by conservation measures. It is a commercially fished species, despite warnings about the huge number of heavy metals and other toxic substances that accumulate in the bodies of grindwales as the final links in the trophic chain.

Northern bottlenose whale

Bottlenose whale (Lat. Hyperoodon ampullatus, Isl. Andarnefja) is a species belonging to the zyphiidae family, which is one of the least understood groups of mammals.

Among other things, the bottlenose whale is one of the record holders in diving. It can descend to a depth of about 2,400 meters, and its dives can last up to 2 hours. Butlogfish feed mainly on deep-sea squid and other cephalopods. They reach lengths of up to 10 meters and can weigh up to 7.5 tons. Due to their long underwater excursions, they can be difficult to observe, but often, with interest, emerge near boats.

Bottlenose whales prefer deeper waters near the coast and are regulars off Icelandic shores. They can be recognized by their relatively small dorsal fin and characteristic convex, massive forehead, where the so-called melon is located. This is a fatty pad used for echolocation and communication. The melon is the feature on the basis of which the sex of the shoebill can be distinguished. Males have larger and more square foreheads, while females and younger individuals have smaller and more rounded foreheads.

White-beaked dolphin

White-beaked dolphins (Lat. Lagenorhynchus albirostris, Isl. Hnýðingur) are animals that grow up to a maximum of 3 meters and can weigh up to 300 kilograms. Their body is rather massive and stocky, and the distinctive features by which they can be recognized are a short, brightly colored “nose” and a darker folded dorsal fin (Van Bree, 1964).

White-beaked dolphins (Lat. Lagenorhynchus albirostris, Isl. Hnýðingur) are animals that grow up to a maximum of 3 meters and can weigh up to 300 kilograms. Their body is rather massive and stocky, and the distinctive features by which they can be recognized are a short, brightly colored “nose” and a darker folded dorsal fin (Van Bree, 1964).

The white-beaked dolphin is a species found only in the North Atlantic, so being in Iceland is a great opportunity to observe them in the wild. They can be found throughout the year. They give birth to young in the summer, so be careful and keep your distance when observing them in the wild. They are herd animals, and groups of up to 10 individuals can often be spotted. These dolphins often join in the hunt for orcas and other dolphinfish, as well as fin whales and humpback whales.

Atlantic white-sided dolphin

White-sided dolphin (Lat. Lagenorhynchus acutus, Isl. Leiftur) is very similar in appearance to the white-beaked dolphin, but is slightly smaller than it. It grows to about 2.5 meters and reaches a body weight of up to 230 kg.

The main feature that allows it to be easily distinguished from the white-beaked dolphin is the characteristic yellowish colored patch on the back of its back.

The area of occurrence largely overlaps with the white-beaked dolphin, and there is a good chance of sighting this species on cruises around Iceland. It is seen more often on the southern coast. It can be found there all year round, but may move around in search of food.

Other species

Other species of cetaceans that we can occasionally see in the waters around Iceland are mainly some whalebone (Biscayan whales, Greenland whales) and toothfish (belugas, narwhals, bowhead whales, common dolphins). With luck, these species can also be observed near the island on a typical “whale watching” cruise (Ingebrigtsen, 2021).

Bibliography

- Cipriano, Frank. (2009). Atlantic white-sided dolphin: Lagenorhynchus acutus. Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. 56-58. 10.1016/B978-0-12-373553-9.00015-8.

- Horwood, Joseph. (2009). Sei Whale 10.1016/B978-0-12-373553-9.00231-5.

- Huggenberger, S., André, M., & Oelschläger, H. A. (2016). The nose of the sperm whale: overviews of functional design, structural homologies and evolution. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the UK. -1. 10.1017/S0025315414001118.

- Kowalski, K., Krzanowski, A., Kubiak, H., Rzebik-Kowalska, B., & Sych, L. (1973). Small zoological dictionary. Mammals Wiedza Powszechna, Warsaw. Poland

- Perrin, W. F., Würsig, B., & Thewissen, J. G. M. (Eds.). (2009). Encyclopedia of marine mammals. Academic Press.

- Bree, P. & Nijssen, Han. (1964). On three specimens of Lagenorhynchus albirostris Gray, 1846 (Mammalia, Cetacea). Beaufortia. 11.

- Langer, P. & Giessen,. (2007). Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M.: Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference 3rd Ed. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press 2005. XXXVpp+2142pp., two-volume set, hardcover: US$125,-. ISBN 0-8018-8221-4. Mammalian Biology – Zeitschrift für Säugetierkunde. 10.1016/j.mambio.2006.02.003.

- Icelandic Whale Watching Association

- Orca Guardians Iceland

- Ingebrigtsen, A.. (2021). Whales caught in the North Atlantic and other seas Rapp. P.-V. Reun. Cons. Int. Explor. Mer. 56. 1-26.

- Mitchell, E. & Reeves, R.R. (1983). Catch history, abundance, and present status of Northwest Atlantic humpback whales Report of the International Whaling Commission. 5. 153-212.

- Reeves, R. R., Silber, G. K., & Payne, P. M. (2021). Draft recovery plan for the fin whale Balaenoptera physalus and sei whale Balaenoptera borealis.